An illustrated essay, which shows how practitioners, including yourself, have addressed social engagement/activism through photography.

In this essay I will be looking at the different methods photographers use to create socially engaged work and the different depths of social engagement that they explore within this. Social engagement in this case refers to how the photographer works with their subjects and audiences. With the subject it is about how they are being portrayed and why; and what the photographer’s motives are in choosing that specific subject. With the audience, engagement happens in different ways; social and emotional engagement are not to be confused, although the two are linked. Social engagement with the audience refers to how they respond and behave as a result of the work, based on their initial emotional engagement, which tends to come first.

I will be looking at my own photography work along with Keith Arnatt’s A.O.N.B. (Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty), both based on the environment but in very different eras. While addressing the same issue we both use similar approaches in terms of social engagement but with different techniques to provoke thought. I will also be looking at two war photographers who show very different perspectives through their photography using different levels of social engagement; photojournalist Robert Capa and also Lalage Snow.

‘Pictures form the battlefield remained substantially the same from the Crimean War of the mid-1850s through to World War I. Photographers concentrated on the aftermath: prisoners, sites of battle, captured material, casualties…The Sino-Japanese War and then the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s were the first to be reported from a combatant’s point of view, chiefly by Robert Capa.’ (Jeffrey, 1997:514)

When thinking about war photography we usually think of the popular photojournalism style, of soldiers in battle or scenes of civilians living with the effects of war. Obviously when this was first recorded by the likes of Capa it would have been incredibly powerful and touching to see this kind of imagery in the public eye therefore it would be deeply emotionally engaging. In this era however, we are used to seeing images from areas of conflict; moreover we are used to seeing video footage on the television so still imagery is not as enlightening to us therefore not as socially engaging as it once was. Also as times have changed and photography became more popular and accessible more of it was available in the press so as viewers became hardened to it, it became somewhat less shocking although the topic was still as devastating. As Jeffrey wrote, Capa was one of the first to record such photography. He began the revolution of photojournalism that so many have followed into.

‘Robert Capa (1913-1954) gave the world some of the most moving and memorable images of war ever taken, and redefined journalism forever. Through his photographs we see suffering, confusion, boredom and courage of the soldiers and civilians affected by the five wars that he covered. Yet he was more than a war photographer: Capa’s portraits of politicians and artists are equally memorable. A participant, not an observer, Capa lived his life on the edge and died in action, killed by a landmine in Vietnam.’ (Lacouture, 2008)

He has captured some of the most powerful images to be recorded in war time history and is often referred to as a legend; mainly because he was willing to risk his life to capture these images as Lacouture writes, and in the end he did. One of the most influential photographs he captured was the Death of a Republican Soldier, taken in Spain, near Cerro Muriano, on September 5th 1936.

Fig. 1: Death of a Republican soldier photographed by Robert Capa (Lacouture, 2008)

There have been allegations of the image being a fake but there is proof that it is authentic and it was Capa’s determination and passion that lead him to be at that place at that time to capture the iconic shot. This is a deeply emotionally engaging image. A perfectly timed photograph of a man seconds after he has been shot; at this time no one would have seen an image of this kind and it is still shocking to see today so would still engage the viewer just as strongly. It is these single moments caught on camera that create the power and increase the social engagement compared to simply documenting what is happening in observational images which we see a lot of today.

In terms of war photography as a whole it is mainly recorded in similar ways with the same kind of imagery reoccurring regularly. Lalage Snow is one of the first photographers I have seen to begin from a completely new perspective aiming to show us the long-term effects of war on individual soldiers in her series We are the Not Dead. She came up with the concept of photographing soldiers before, during and after their deployment in Afghanistan to show us the changes close up. There are obvious changes at each stage and it is clear there are alterations deeper than those we see on the surface. In the photographs taken during their deployment the soldier’s faces seem tired and lifeless. Despite their eyes being sunken and lost in deep bags with depressed wrinkles there is a fire we can see in their eyes; this is what they are there for and what is keeping them going. The eyes alone tell a thousand words here. These soldiers have clearly changed. That is what makes these images so powerful; the fact we can tell all of this from very simply composed portraits. Here it is not so much about the technicalities and the skill involved, although they are obviously needed. Rather it is the subject that tells us everything. Snow has in fact been criticised for allegedly ‘posing’ the subject while in Afghanistan using artificial lighting to give a different appearance but she explains in an interview online that this is not the case:

‘The before and after shots were taken in an army barrack room outside Edinburgh so the light is cold and Scottish. The light in Afghanistan is very special and a world away from Scotland.’ (Cited in: Pinar, 2013)

This is another element that shows us a difference in the environment and how the soldiers’ worlds differ to ours, increasing the level of social engagement with the audience. This series is engaging in a number of ways; it directly involves the soldiers participating to create a subject and a narrative in this case. This engages the soldiers and provides them with a way to tell it “how it is” to the public. The images alone provide deep emotional engagement but Snow furthers the social engagement by speaking to the soldiers to deepen her, and our, understanding of their situations and the changes they have faced. Snow asked each person how he or she was feeling about their situation at each stage, which draws attention to the psychological alterations of the soldiers, not just the physical; another dimension to this project that we rarely see in other examples.

Fig. 2: A triptych from Snow’s series ‘We Are The Not Dead’ (Pinar, 2012) Accompanying interview follows:

‘Lance Corporal Sean Tennant, 29: 11th March, Edinburgh

“I am looking forward to getting back and for the 6 months to be over. All this talk of being excited to get out there is rubbish. The younger lads will get a shock. I am going to miss flushing toilets and having a long shower whenever I want.”

11th June, PB Zeal, Nad Ali

“I can’t remember how long I have been here. I was in Babaji before where our compound was under fire a few times. I wasn’t scared though as I have been shot at plenty of times before in Iraq. IED’s are the biggest scare here though. It takes a while to get used to that – and when you are on the ground you eventually realise that not every step you take is going to blow you up.”

6th October, Edinburgh

“You see them firing at you and it’s like a Mexican stand off. But it’s always an ambush so you get a fright to start with but you just deal with it. You try not to think about it too much otherwise you get yourself wound up. Are we making a difference? On of my friends died and then there are all the boys who’ve been injured… It isn’t worth that. Its great being back but I’d say I’ve got a shorter fuse now. I ended up arguing with my partner but it’s small things that can cause that. It’s a funny one. There are small things that can get on your nerves. Supermarkets are bad because there are bright colours and everyone walks about like lemmings. It seems like people don’t have any purpose here.”’

Snow gives the often “silent” soldiers an opportunity to speak out about their experiences, which also increases the social engagement; viewers are more inclined to read their stories to feel like they understand the soldiers more as a result. An authors’ response online is just one example of what can be learnt from this project,

‘Having gone through life-altering trials and warfare, it is no surprise that fear is no longer a foreign feeling to these courageous men.’ (Pinar, 2012)

It is a much more personal and deeply engaging style of photography than any war journalism; we rarely see such an intimate look at individual soldiers, especially when we compare this kind of work to that of the early war photographers such as Capa. The name is so apt We Are The Not Dead as sadly often the only way we hear about individual soldiers is when they have died in action, so it is refreshing to learn personally about the ones who have survived. It is also very thought provoking as death is something many people do not like to talk about, so this again deepens the social engagement.

Social engagement can happen through photography in different ways, the same methods can be transferred between very different subject matter. Just as Robert Capa documented what he saw in different wars through photography, for use in newspapers and magazines, Keith Arnatt, also documented what was in front of him, to show to other people and “spread the word” of the subject matter in his series A.O.N.B. (Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty), 1982-84.

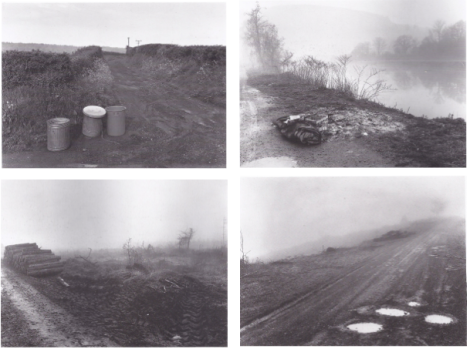

Fig. 3: Four images from Keith Arnatt’s series ‘A.O.N.B (Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty)’ (Mostyn, 1989)

‘Fascinated by the concept of “official” beauty spots and the impact of human traffic upon them, Arnatt used this series of scenes of the Wye Valley (photographer using a 4×5 view camera) to play with the ideas of beauty and our expectations of the landscape photograph.’ (Hurn, 2007)

On first sight Arnatt’s photographs appear to be making a plain statement about the environment and the way it is treated, by creating an image in which the subject is something unnatural and somewhat of an eyesore that juxtaposes the beautiful landscape behind. However, they have deeper meaning than that. These images are all taken in the Wye Valley where Arnatt grew up making them sentimental to him, when we understand more about how the images are taken we can see the connections and why he has chosen this location to engage with the viewer. Rather than choosing to shoot these images on a bright sunny day Arnatt has taken each one on very dull, misty days when the landscapes are not looking their best; as Hurn wrote he was playing with our ‘expectations of a landscape photograph’ (Hurn, 2007). Due to this we cannot see as much of the landscape as we’d like to, Arnatt restricts the viewer. I think he does this to make us look at the other elements that make the landscape a beautiful place other than the visual appearance of it. Each of the subjects in the images could have great sentimental value to Arnatt; places he used to go as a child that remind him of people or memories. They are all part of what makes the place special to him. In this sense Arnatt is deeply engaging with himself and his own past to revisit this place and photograph it in a different way, which represents him within the landscape for other people to see and try to understand. (Mostyn, 1989)

‘The Wye Valley is also a place where people live and work. A.O.N.B. is not simply ironical; it is also an affectionate portrait of a lived-in Wye Valley, a place Arnatt himself has inhabited for twenty years, and which he knows intimately. When Arnatt depicts battered dustbins or sodden rolled-up carpet on the edge of the river, it is too easy to read his intentions as ecological, a straightforward denunciation of the despoliation of the countryside. Those objects are as much part of his experience of the Tintern as the tea shops, the picturesque cottages and the Abbey, however much the casual viewer may want to overlook them. Arnatt really likes those apparently insignificant pieces of detritus and, in this regard, he is heir to a 20th century artistic sensibility, traceable through Schwitters and Rauschenberg, which values “rubbish” for its visual richness, its connotations of history and memory, social and personal use.’ (Arnatt, 1989)

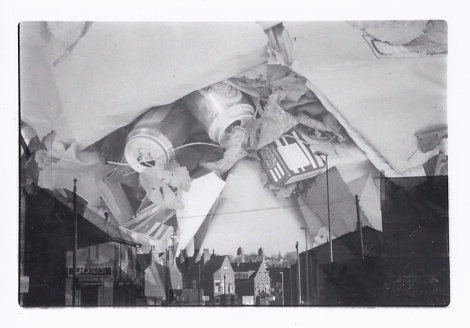

I have created a series of images that address disrespect for our environment predominantly through littering and fly tipping. The project has similarities to both Capa’s work and Arnatt’s series A.O.N.B. I have documented things that I have found around Leeds that show a lack of respect for the environment, it was worryingly easy to find things to photograph. I coupled images of litter with that of a cityscape, using double exposure technique to get both parts in the same image. The litter represents the disrespect and negativity of people’s attitude to our environment. While the cityscapes represent the people and the cause of the problem. I have composed them in a way that litter appears to be coming down from above onto the city and overtaking it; the images are quite dark as a result of this but I like this as it adds to the negative feel of the imagery making it more powerful.

Fig. 3: My own photographic series Rubbish Leeds.

It is socially engaging in the respect that it documents the actions of people; without their input it would not work, although similarly to Capa and Arnatt’s work the people are not directly involved. I have taken photos of this to show to the people of the area to bring the issue to light through photography in the hope that they will recognise the negative effect it has on the city to make a change. This is socially engaging as it affects lots of people so can have a powerful knock on effect. In comparison to Lalage Snow’s series it is far less socially engaging as it does not have direct input from anybody else. To increase social engagement I should speak to people first hand about the issue to get their opinions and discover why it happens, maybe nobody cares enough about the area to want to change. I don’t think it is necessary to change the imagery to involve people as a subject in the image but to add text similarly to how Snow has it could be much more powerful and improve the series in terms of social engagement.

The subject of littering and the environment is not as emotionally engaging as war, so will never have the shock factor or emotionally engage in that sense. Rather it is something that provokes deeper thought and questions our own actions in regards to our respect and attitudes towards nature. I think my images show a lack of respect to the environment because Hyde Park is a heavily student populated area; most of the people living there live “part-time” so are naturally less likely to grow an attachment to the place, which leads to a lack of care for the location. It could also be due to the age of most of the people in the area that it is not being paid the respect it should. The average age of people living in Hyde Park and Woodhouse is 27 with the median being 22 according to the 2011 census (Qpzm, 2012). This shows contrasts with Keith Arnatt’s work, which focuses on an area that the photographer is deeply connected with. Even in this instance however there are signs of disrespect for the landscape; which probably appears more emotionally engaging as they are Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty which are instantly thought of as being more precious and needing more care taken of them. It proves that no matter where you are there will probably always be some signs of disrespect for the environment, which comes from the peoples, mainly the residents, actions therefore it is important that these projects should be emotionally engaging to change their mind-sets to make a social change, which in turn makes the images socially engaging if they are having an impact.

Perhaps work by women, i.e. Snow and I, is different and aimed at being more emotionally engaging coming from a woman’s perspective. Therefore males and females in the audience would receive the response differently. Females tend to stereotypically be more sensitive and show more emotion so would engage emotionally more strongly with the images and the message than men. If emotional engagement is more of a female trait it is expected to have a stronger response from them. I still feel that there are differences according to the subject of the piece. I would assume that as a whole, the majority of people feel more emotion towards human matters e.g. War, in which peoples lives are regularly put at risk, than environmental issues so I would expect a larger response in terms of engagement both emotionally and socially to Capa’s and Snow’s work than mine and Arnatt’s. Perhaps this is why a lack of respect for the environment exists in such a large way.

Lalage Snow’s work We Are The Not Dead is very socially engaging as she relies entirely on having the input of the people she is photographing; without them her project would not exist. She interacts with them personally and makes connections to create her images, which is what makes her series so socially engaging; the subject’s input is vital. Arnatt’s work therefore, and my own, are both far less socially engaging. We have not used people in the images nor have we needed their direct input to create the images. However, in both series we have photographed the actions of people and their mark on the environment. So we still could not have created them without people. This makes the work socially engaging in different ways. Capa’s work is socially engaging in a similar way, he relied on soldiers in his war photojournalism to create a subject and something to document but he did not make deep connections visible through the images. My series aims to document what people have left behind in a negative way, disrespecting the environment while also representing the cause of that in the image through double exposure.

Bibliography

Books

Hurn, D & Grafik, C. (2007) I’m A Real Photographer, London, Chris Boot Ltd. pp28-37

Keith Arnatt (1989) Keith Arnatt Rubbish and Recollections, Llandudno, Oriel Mostyn.

Jeffrey, I. (1997) The Photo Book, London, Phaidon. pp514

Lacouture, J. (2008) Robert Capa Photofile, London, Thames & Hudson

Shea, A. (2012) Designing for social change: strategies for community-based Graphic Design, New York, Princeton University Press

Soles, D. (2005) The Academic Essay: How to Plan, Draft, Write and Revise, 2nd Edition Edition. Studymates Limited.

Websites

Magnum Photos (2012) Magnum Photos Photographer Portfolio, [Internet] Available at: <http://www.magnumphotos.com/C.aspx?VP3=CMS3&VF=MAGO31_10_VForm&ERID=24KL535353.> [Accessed 13 January 2014].

Qpzm. (2012) Hyde Park and Woodhouse Demographics (Leeds, England) [Internet], Qpzm postcodes. Available from: http://localstats.qpzm.co.uk/stats/england/yorkshire-and-the-humber/leeds/hyde-park-and-woodhouse [Accessed on 13th January 2014]

Pinar. (2012) Portraits of Soldiers Before, During and After War [Internet], My Modern Met Blog. Available from: <http://www.mymodernmet.com/profiles/blogs/lalage-snow-we-are-the-not-dead> [Accessed on 23rd November 2013]

Pinar. (2013) More Portraits of Soldiers Before, During, and After War + Interview [Internet], My Modern Met Blog. Available from: http://www.mymodernmet.com/profiles/blogs/lalage-snow-we-are-the-not-dead-interview [Accessed on 10th January 2014]

Snow, L. (ND) We Are The Not Dead [Internet], Lalage Snow Galleries. Available from: <http://lalagesnow.com> [Accessed 23rd November 2013]

Images

Fig. 1: Lacouture, J. (2008) Robert Capa Photofile, London, Thames & Hudson

Fog. 2: Pinar. (2012) Portraits of Soldiers Before, During and After War [Internet], My Modern Met Blog. Available from: <http://www.mymodernmet.com/profiles/blogs/lalage-snow-we-are-the-not-dead> [Accessed on 10th January 2014]